Global carbon pricing & COP26: a primer

How global carbon pricing works, why COP26 is instrumental for implementing it, and what a global carbon price would mean for businesses.

Emitting greenhouse gases has a steep cost – a climate cost. Historically, this cost has largely been paid by the public, which has had to deal with negative externalities like the destruction of property due to rising sea levels, the health impacts of polluted air, and the devastation to communities wrought by severe weather events.

By charging emitters for the carbon they release into the atmosphere, carbon pricing aims to move the cost of carbon emissions back to its source: the emitter.

“Carbon Pricing effectively shifts the responsibility of paying for the damages of climate change from the public to the [greenhouse gas] emission producers.” – UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

What carbon pricing accomplishes

While there are many types of carbon pricing – the most-used of which we’ll detail below – what all carbon pricing initiatives have in common is that they encourage emissions reductions by applying a financial cost to emissions.

This encouragement is especially impactful in the private sector, where companies who may not be motivated to reduce their climate impact for altruistic reasons would, with the implementation of carbon pricing, have a clear financial case for making climate-friendly changes.

Carbon pricing also supports the development of innovative low-carbon tech, giving it a financial leg-up in the competition to unseat established, carbon-heavy technologies.

“Putting a price on carbon can encourage low-carbon growth and lower greenhouse gas emissions.” – UN Global Compact

Where do the revenues from carbon pricing go?

Exactly where the revenues from carbon pricing ought to go is a matter of debate.

Some believe that the increased cost to businesses will be passed along to consumers, and thus advocate redistributing the carbon pricing revenues as direct payments – or stipends – to the citizens of the countries the revenue is collected in.

Others believe the revenue should be re-invested in climate technology or in grants for environmental research.

And some call for for a compromise between those measures; e.g., supporting low-income households and those likely to face economic harm from the measures with retraining and a strengthening of social safety nets. The rest of the revenue would be invested in green initiatives.

Types of carbon pricing

There are many forms of carbon pricing, all of which aim to incentivize the reduction of emissions. Some of the most common are summarized below.

Emissions trading systems (cap-and-trade)

An emission trading system (ETS) – also known as cap and trade – sets a limit for how much carbon can be emitted, then issues emissions permits equal to the limit which can be bought and sold. This lets the law of supply and demand set the price of emitting.

If you’ve ever bought a concert ticket, then you’ve participated in a system like this. The concert venue can sell only as many tickets as there are seats. Once the seats have been sold out – e.g. the supply of seats has been exhausted – then the only way to get a ticket is to buy one from someone who’s selling it. The amount of people who want to go and the strength of their desire – e.g. the demand – sets the price.

China is in the process of establishing a national ETS. When this system is implemented it will be the largest such system in the world, covering more than 4 billion tons of CO2 emissions.

Carbon taxes

A carbon tax is similar to other taxes in that it levies a price on something, in proportion to that something’s size. In the case of carbon taxes, what’s being taxed is greenhouse gas emissions.

Unlike emissions trading systems, a carbon tax can’t guarantee a maximum level of greenhouse gas emissions. But while it lacks the ability to set a hard ceiling to emissions, a carbon tax does have the advantage of being simpler to understand and implement, compared to ETS.

The Canadian province of British Columbia has a carbon tax that covers 70% of the province’s total greenhouse gas emissions. The tax is revenue-neutral, which means that the money earned from the tax is returned to the citizens via reductions to other taxes (like income and property taxes).

Emission reduction funds (ERF)

Emission reduction funds allow companies to generate credits by implementing new initiatives to reduce their emissions. They can then sell these credits to the government.

Hybrid approaches to carbon pricing

Some governments implement a blend of carbon pricing measures.

One common hybrid method is a cap-and-trade system, with floors and/or ceilings to the trading price of emissions permits. This pairs ETS’s ability to regulate the amount of emissions with carbon taxing’s more predictable revenue.

In the example of South Africa, the carbon pricing approach allows emitters to buy offsets to reduce their carbon tax liability.

Global carbon pricing

The situation today

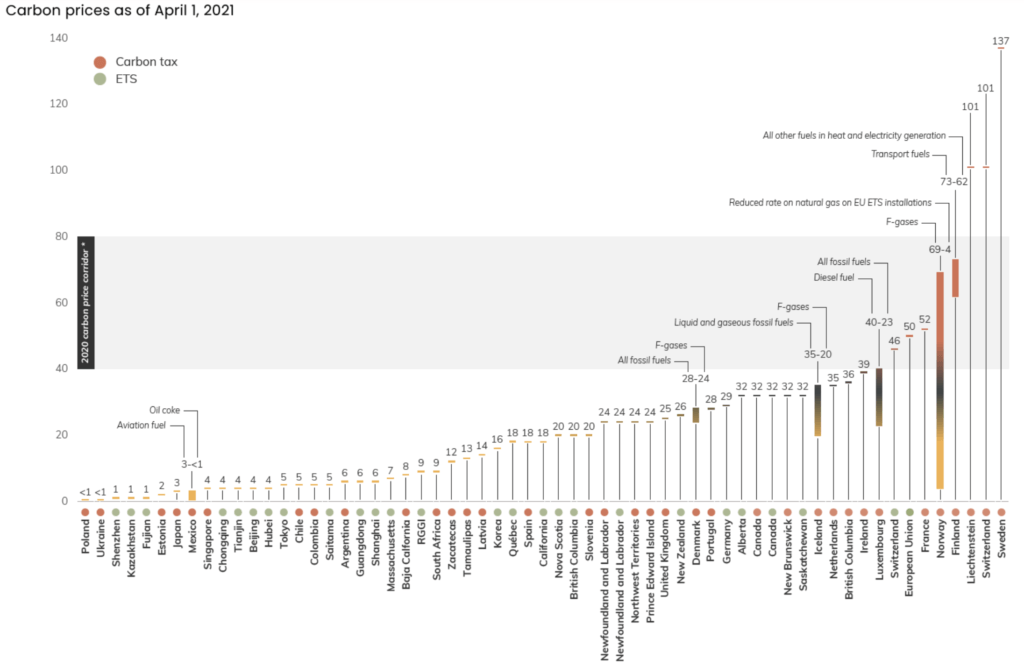

64 countries currently have some form of carbon pricing implemented. These carbon pricing programs cover only about 20% of global emissions.

The current global average price of carbon is €2.50 per ton – though the OECD has estimated that a price of €125 is needed before 2030 if the world is to reach net zero emissions by 2050. Even the country with the highest carbon price in the world, Sweden (Normative’s home country), has a carbon price of only €116 per ton.

The need for a global solution

For carbon prices to function the way they’re intended, they need universal adoption. Gaps in coverage could allow emitters to dodge their country’s carbon pricing by moving their emissions to countries without carbon pricing and importing their products back.

While there is currently no global carbon price, support for a truly global solution is increasing in both the public and private sector.

More than 100 countries have expressed interest in using carbon pricing to meet their Paris Agreement Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets.

In the EU, the OECD recently announced a new global carbon pricing plan that aims to resolve the import loophole. Under the OECD’s proposal, a hybrid ETS carbon pricing initiative in the EU would set a minimum cost for carbon, and raise that cost over time to incentivize Paris-aligned emissions reductions. Imports to the EU from countries with no carbon pricing would face a carbon tax.

Senior officials in the U.S. – which has no national carbon pricing, and a history of holding out when it comes to global trends in climate policymaking – have signalled openness to considering measures like carbon taxing.

And in the private sector, a UN-convened group of investors responsible for managing more than €5 trillion in assets has called for a coordinated global carbon price.

Following the sixth IPCC report – the panel’s most dire climate warning yet – pressure is mounting for COP26 to result in strong and global climate measures. Though carbon pricing will not miraculously solve the issue of climate change by itself, it is a useful starting point for governments to take to take decisive, coordinated action.

Can COP26 result in a global carbon price?

The UN and carbon pricing

The UN has previously supported carbon pricing.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement provides a framework for ETS, stating that an international carbon pricing initiative could result in a greater magnitude of emissions reductions than solely national measures. The proposed framework is meant to increase transparency in emissions accounting, and prevent double-counting of emissions across borders. But this framework has yet to be implemented.

Soon after the signing of the Paris Agreement, the UN Global Compact called for businesses to put a price on carbon at €85 (USD $100) per metric ton. This, too, has yet to be implemented.

What could COP26 actually deliver?

Beginning 31 October, the 26th UN Conference of the Parties (COP26) will gather world leaders and policymakers to discuss issues related to the global climate.

For a detailed history of the COP, see the first article in our Road to COP26 series

While COP26 – and the Conference Of Parties in general – does not dictate policy to countries, together COP actors can set targets that countries can commit to. In theory, this would lead to countries setting domestic policy to meet those targets. But, as we’ve seen in the wake of the Paris Agreement, treaties and resolutions without enforcement mechanisms can be ignored when inconvenient.

Put plainly: COP26 can’t set a global carbon price, but it can bring together world leaders, recommend that they set a global carbon price, and provide a forum to allow them to discuss it.

How businesses can prepare for carbon pricing

To prepare your business for the possibility of future carbon pricing, your first step is to calculate your emissions. These will likely need to be reported in a standardized format.

Once you have an overview of your emissions, you’ll be able to identify hotspots in your emissions profile – e.g., suppliers or activities that generate a disproportionate amount of greenhouse gas. Identifying your emissions hotspots means you can begin to transition away from them.

Even if COP26 doesn’t result in newly imposed carbon pricing, knowing your emissions and taking steps to reduce them should be a goal for every company.

The climate is changing drastically, at great economic and well-being cost, and business emissions are contributing to the problem. That fact holds true whether or not the COP26 and national governments are able to implement global carbon pricing. Rather than waiting for government mandates, we encourage every business to begin policing its own carbon usage.

Calculate & reduce your carbon emissions

Normative’s emissions accounting engine shows your company’s entire climate impact – including your supply chain – and highlights the highest-impact actions you can take.